1st Pillars Conference on Education, Skills, and Worker Retraining

Until just a few decades back you could count on the education you got in college seeing you all the way to retirement. Now, you have to reinvent yourself professionally several times during your working life just to stay current. Lifelong learning is the name of the game, and training and re-skilling the tools of choice.

Exploring the many aspects of this new reality was the topic of the PILLARS inaugural conference, encapsulated under its Education, Skills and Worker Retraining heading. The proceedings were divided into eight sessions that discussed two dozen papers over two days, with topics covering a wide range of labour market challenges and a number of geographical locations. You can review the program here.

But the conference offered much more than just discussing ongoing research: it gave junior researchers a superb opportunity to interact directly with senior researchers. For one thing, the PhD papers presented always had as discussant a seasoned scholar. For another, special Junior-Senior Sessions were organized to bring together junior researchers with each of the two keynote speakers, Sandra McNally and Eric Hanushek, one held on the conference’s second day, the other about a week later.

Sandra McNally, of the University of Surrey, promptly delved into the core of the overall topic in her keynote speech, devoted to Training and Re-Skilling in the Labour Market, by reviewing current research on many aspects relevant to this pursuit (for a summary see below).

At the end of the second day of the conference, Eric Hanushek, the doyen of the economics of education, gave a keynote speech full of insights on Lifelong Learning and Dynamic Adjustments to Changes in the Labour Market (for a summary see below).

The proceedings wrapped up with a tasting of fine wine that had previously been shipped to all participants. The clinking of glasses was virtual, but the wine itself tasted really, really good.

The PILLARS researchers, who have clearly been quite busy since the project’s inception, will now have to start cramming for the mid-terms. Once they are sober again, that is.

For more information watch the video about the conference and the innovative data and research presented.

Keynote Speech Summary

Sandra McNally: Training and Re-Skilling in the Labour Market

When it comes to devising public policy interventions, there must be clarity regarding both the reasons for introducing such policies and the possible risks associated with them. The first questions to look at are “What are the returns?” and “Where are the gaps?”.

In labour markets facing disruption through globalisation, technological change and digitalisation, inequality can grow wide, with Intermediate and low-skilled people as the most likely to be disadvantaged. Furthermore, with people living longer, we will all have to engage in learning much more than in previous generations. Assuming that training can lead to better outcomes, we need to identify how training can help, how to lower barriers to training for people on low incomes, and how to address externalities (such as not enough provision of training).

We also must pay attention to the risks, such as not providing the right skills, or if we end up not changing behaviour enough. Both would lead to significant waste and would become hard to justify (“deadweight”). As an example, Sandra mentioned the UK Employer Training Pilots. It looked flawless: free training, paid time off for training, wage compensation, information advice and guidance. And yet, no effect on take up in three years. The apparent reason is that things were done that would have happened anyway. Another example was a GM factory in Janesville, where training did not help, since it was not provided in the right things.

A further complication is that we know less about returns to training than we do about returns to formal schooling. What we do know, though, is that training and formal adult education are very heterogeneous within and across countries, and are therefore difficult to translate. Training does not travel well.

So, what lessons has research identified?

Active labour market policies can have small or even negative short-term impact, but larger impact on the medium and long term (increased probability of employment: 6-7%). The so-called sectoral training programmes in the US, which are specifically geared to the needs of the local employers and are managed by community organisations, seem to address the shortcomings of the Janesville case (which was training in a vacuum). The short- to medium-run impacts on earnings scored about 20%. An LSE study found that shorter programmes are more effective and that training that reflects actual jobs works better.In some contexts, training on interpersonal skills leads to higher returns than training in technical skills. Soft-skills are particularly relevant for people on low-skilled occupations. In general, research has shown that linking skills in curricula to labour markets leads to much better outcomes.

What do we know about policies and practices?

Individual incentives, such as through training accounts, subsidised training, tax deductibility for training expenses, seem to offer good returns, just as when human capital development is treated similar to R&D. Other approaches that seem to work well are boot camps, as well as novel models for conferring non-degree credentials and understanding how adults learn.

Keynote Speech Summary

Eric Hanushek: Lifelong Learning and Dynamic Adjustments to Changes in the Labour Market

When the effects of automation, robots, and AI are discussed, the focus so far tends to be on costs and harm. Less is said about what can be done to lessen potential harm, which leads to the idea of lifelong learning.

Here vocational education plays a key role, but the views on it around the world differ widely: from being eliminated in the US (and resurrected by Trump) to much more reliance on it in Europe (with Germany often cited as an example of successful application of vocational education leading to employment).

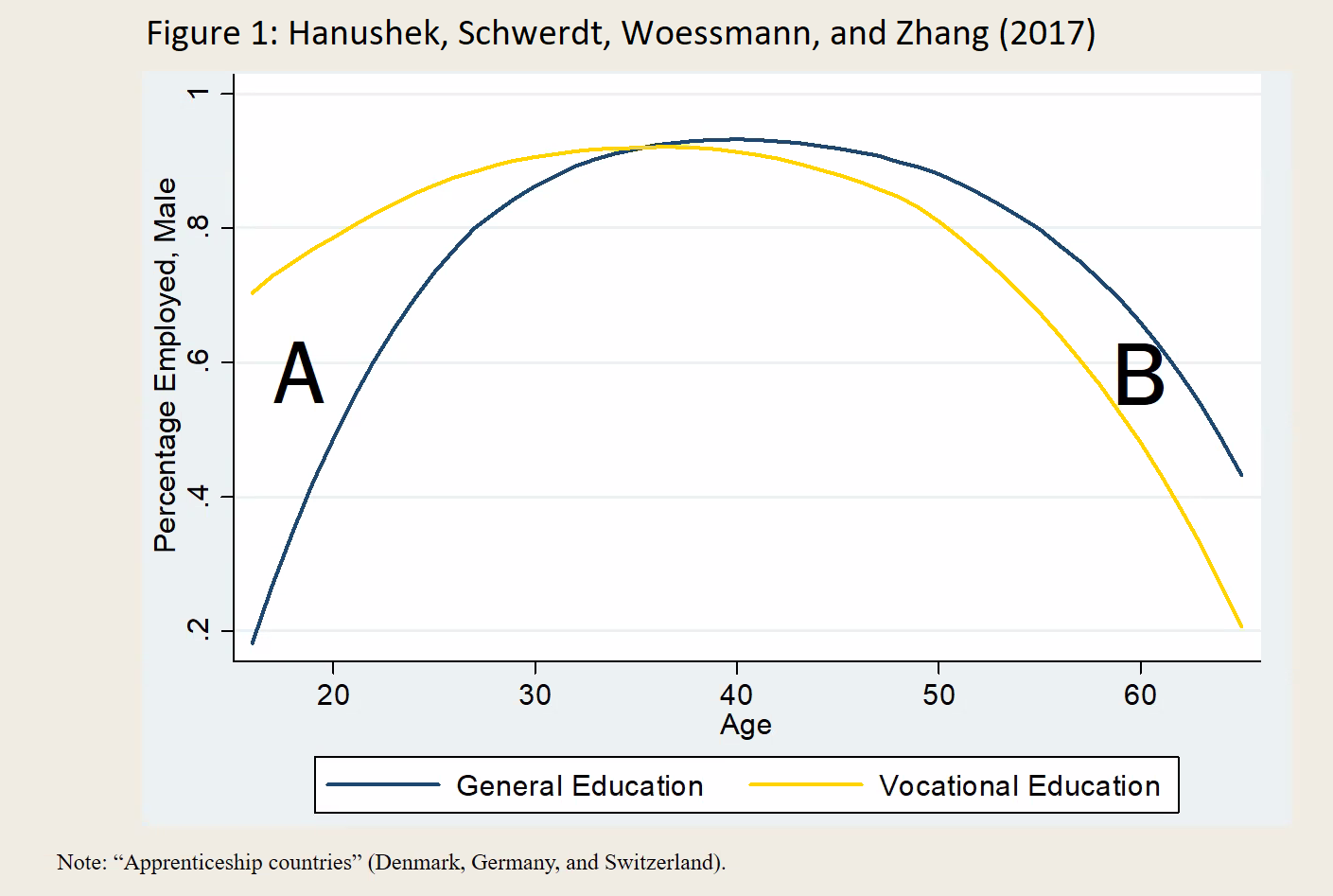

Strikingly, a study led by Eric and Ludger Woessmann with their colleagues Guido Schwerdt and Lei Zhang, showed that the returns to vocational education taper off in the later years of the working life (Figure 1).

The reason could be skill obsolescence, not keeping up with technological developments, or maybe different retirement planning.

But when it comes to discussing the related issue of lifelong learning, it is often more slogan than reality, with details seldom provided. Encouraging adult education is one of the ideas being floated, but usually accompanied with many as yet not properly answered questions: Should employers be incentivised to be more active in training their employees? What if employers countered with why should they retrain a middle-aged employee when they could more easily hire a younger one? So, should incentives be provided to employees instead? Or should training be government provided?

In view of this, Eric and his colleagues looked at it from a different standpoint. Starting from the fact that while the net aggregate effect of robots, trade and AI disruption may be zero or even positive, this is not true for individuals. Their proposal turns worker displacement on its head, by taking a cohort of young workers and focusing on adjustments before plant closures occur.

Knowing that the world will change for displaced workers, do they invest in enhancing their human capital? Do they get a payoff of that investment? Should they pursue other adjustments before closures? Who exactly should adjust?

To find out, Eric and his colleagues examined integrated employment histories (such as those available in Germany), with unique person and establishment identifiers, taking a sample that included people who completed first apprenticeship or started their first job between 1995 and 2010, mainly from large firms, observing plant closures 5+ years after employment entry, and dividing their “universe” among early adjusters, late adjusters, and controls (“stayers”).

Given that the terminology can be somewhat confusing, a clarification: with “Late adjusters” is meant people who do adjust, instead of jumping ship at least a year ahead of plant closure; those that jump ship early would be the “early adjusters”, and in Eric’s study are not being taken into account as people reacting to the disruption itself; they are likely simply bad job matches. Late adjusters, in contrast, take the hint and start investing in reorienting themselves occupationally before the plant closure approaches.

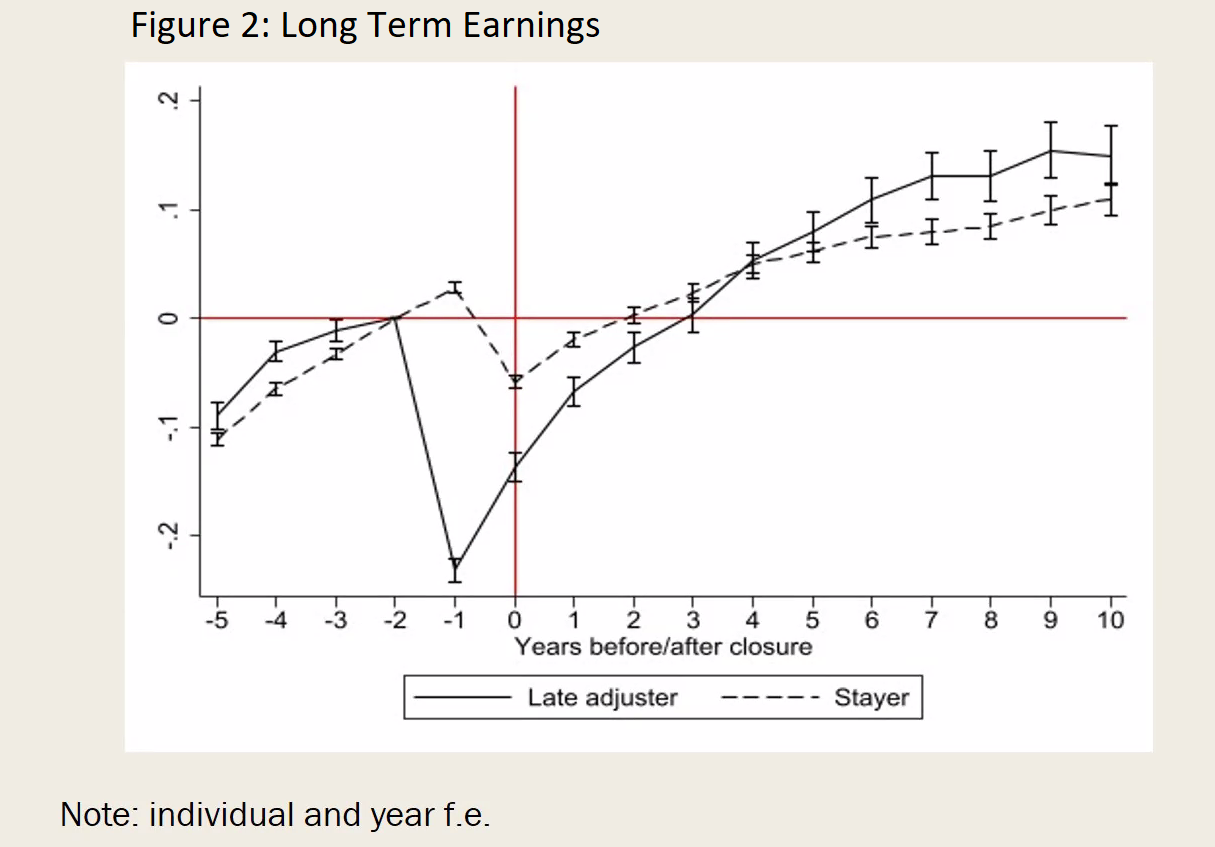

The researchers then make a comparison between stayers vs. late adjusters (Figure 2).

Late adjusters experience a huge loss of income immediately, but then they climb up afterwards and end up overtaking stayers in income. Adjusters, in other words, do better over time.

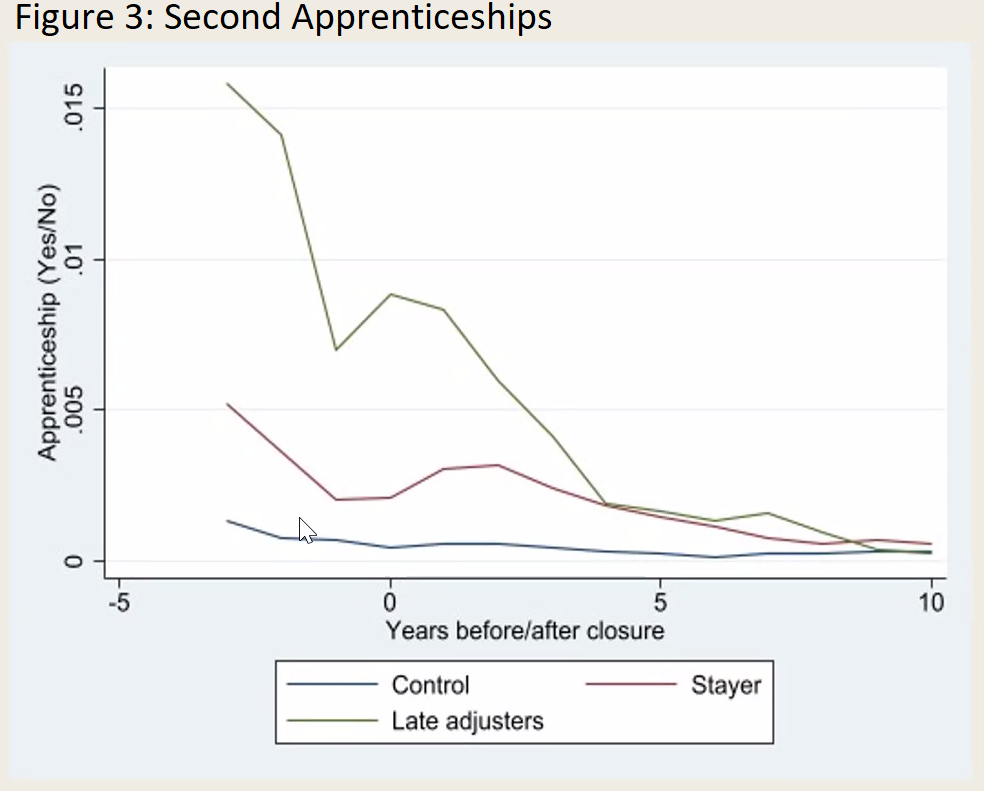

In terms of second apprenticeships, late adjusters do a lot more in terms of getting new training (Figure 3).

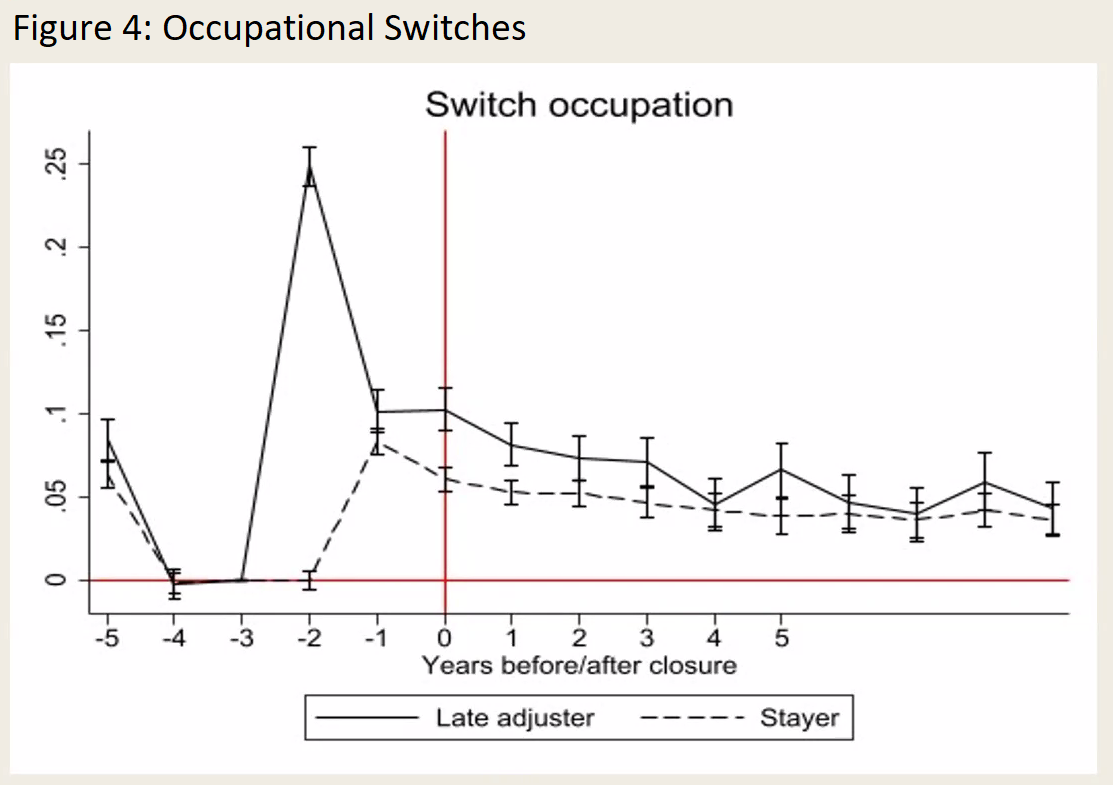

Late adjusters are also much more likely to switch occupations with plant closures (Figure 4).

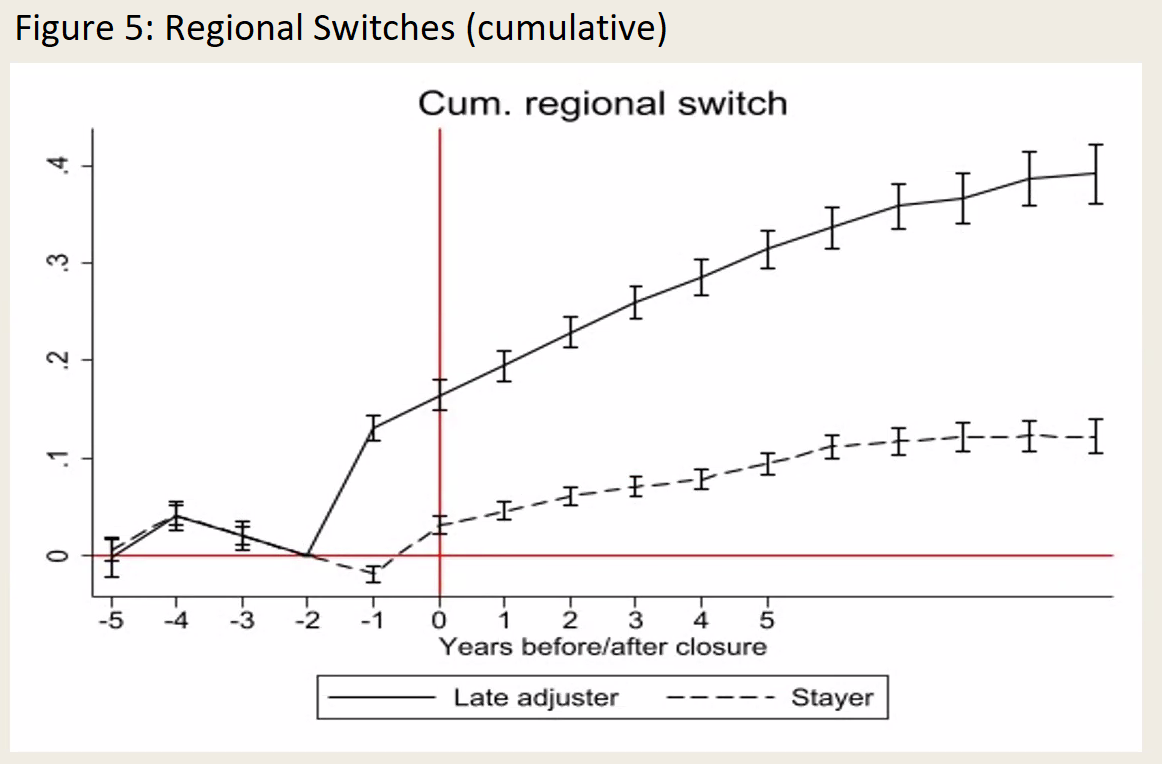

Late adjusters are much more likely to switch regions, compared to control (Figure 5).

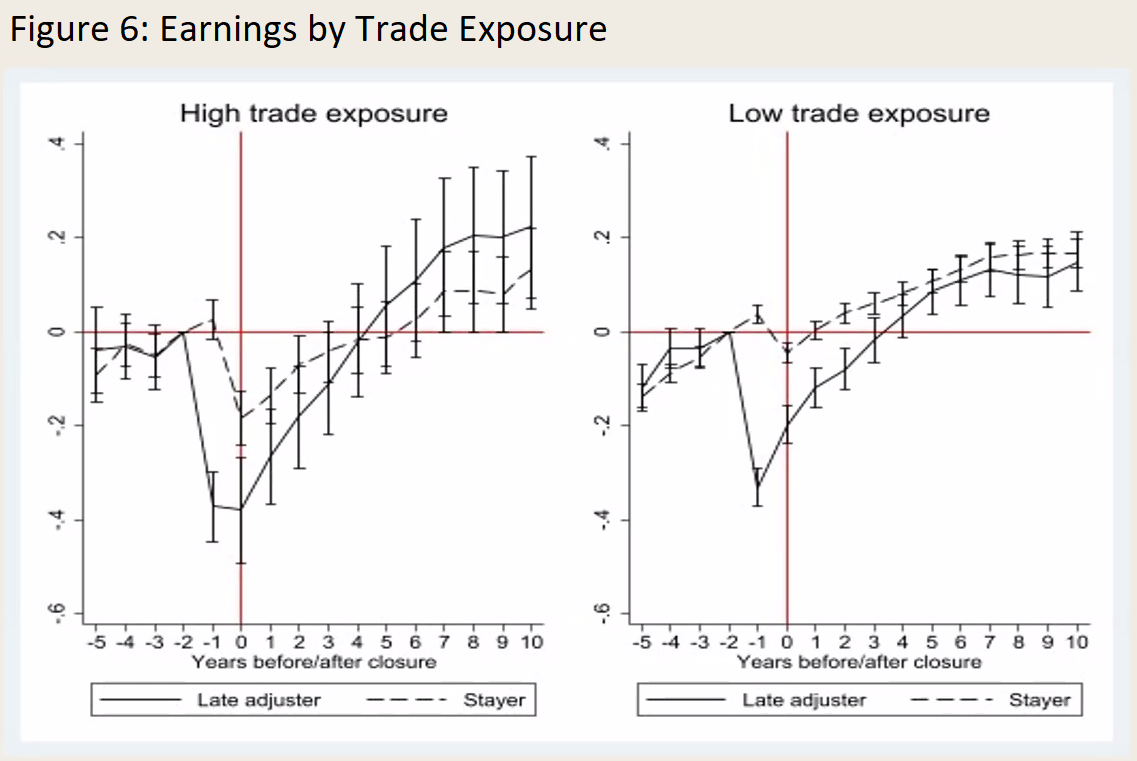

How about external disruptions, such as the often-mentioned robots, AI and trade? Well, robots are mainly employed in the automobile industry, so the authors won’t focus on them. As to AI, it is a bit early days yet. Thus, their focus is on trade exposure (Figure 6).

By being in “risky” industries (more exposed to trade), late adjusters are led to make more changes to their occupation compared to those in low exposure industries.

The upshot is that late adjusters make larger adjustments (occupational and regional in nature), a trend that is amplified when being in risky/threatened industries (trade exposed). They also invest more, in such things as second apprenticeships or going back to university. Their reward is that they recover pre-event earnings after disruption and major changes, and then some.

Despite these findings, more research is necessary (isn’t it always?) to further refine strategies to help workers cope with disruptive occupational changes.